A dynamic urban powerhouse, Mexico City pulses with energy—where historic cantinas meet cutting-edge cuisine, world-class museums spark curiosity, and boats glide through ancient canals. It’s the cultural and political heart of the nation, the center around which all of Mexico revolves.

As the seat of Mexico’s federal government, the Palacio Nacional (National Palace) houses the offices of the president and the Federal Treasury. It’s also home to the renowned Biblioteca Miguel Lerdo de Tejada, one of the country’s most significant libraries, with interior walls adorned by striking murals. But for many visitors, the main attraction is the palace’s extraordinary collection of murals by famed Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

Historical background

This site originally held the palace of Aztec emperor Moctezuma II in the early 1500s. When Hernán Cortés conquered Tenochtitlán in 1521, he destroyed the Aztec structures and documented their grandeur in letters sent to the Spanish crown. Soon after, Cortés commissioned the construction of a new fortress on the site, featuring three interior courtyards.

In 1562, the Spanish crown purchased the property from Cortés’ heirs to serve as the residence of the viceroys of New Spain. Following Mexican independence, the building’s name changed from Viceroy’s Palace to National Palace in honor of the country’s new era of self-rule.

One of its most iconic features is the Campana de Dolores—the bell Padre Miguel Hidalgo rang in Dolores Hidalgo in 1810 to signal the start of Mexico’s War of Independence. Today, it hangs above the central entrance. Every year on the night of September 15, the president steps onto the balcony below it to deliver the grito—a rousing “¡Viva México!”—to mark the country’s Independence Day celebrations.

Diego Rivera’s ‘The History of Mexico’

Between 1929 and 1951, Diego Rivera painted a breathtaking series of murals within the palace, collectively titled The History of Mexico. These large-scale works span the walls of the main courtyard’s upper level and illustrate Mexico’s evolution—from the mythology of Quetzalcóatl and the life of pre-Hispanic civilizations, to the Spanish conquest and the struggles of the post-revolutionary era.

Seeing the murals for the first time is an unforgettable experience. Their color, detail, and sheer scale are a dramatic visual journey through centuries of Mexican history.

Visitor information

As of 2022, general public access to the Palacio Nacional is restricted under current government policy. However, some authorized guided tour groups may still be allowed entry, and virtual tours are available online via Zoom.

Once the tallest building in Latin America when it was completed in 1956, the Torre Latinoamericana still dominates the skyline of Mexico City’s Centro Histórico. More than just an architectural icon, it serves as a helpful landmark when navigating the downtown area.

Construction and resilience

Built on deep-set pylons, the Torre has withstood the force of several powerful earthquakes, including the devastating quakes of 1985 and 2017. Its structural stability has become a point of pride and a testament to forward-thinking engineering.

Visiting the Torre

The views from the 44th-floor observation deck are remarkable—offering a panoramic sweep of the city that reveals its massive scale, especially when the skies are clear. The 41st-floor lounge bar also offers excellent views in a more relaxed setting.

Tickets cost M$170 for adults and M$100 for children, and you’re welcome to leave and re-enter throughout the day—making it easy to experience the skyline by day and again at night, when the city lights come alive. The ticket also includes entry to an on-site museum that traces the history of Mexico City.

If you’re only visiting the bar, admission is free (you’ll just need to purchase a drink). There’s a dedicated elevator for the bar, which is a great option if the line for the observation deck is long.

Before the Spanish conquest, the Templo Mayor—or “Great Temple” of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán—stood as the heart of the city. It occupied the area now beneath and around the Mexico City Cathedral, stretching across blocks to the north and east. Though much of it was lost to colonial construction, the temple’s significance was rediscovered in 1978 when electrical workers unearthed an 8-ton stone disc depicting the Aztec moon goddess Coyolxauhqui. This major discovery prompted the demolition of several colonial-era buildings to allow full-scale excavation of the site.

According to Aztec mythology, this was the very spot where the Mexica people witnessed an eagle perched on a cactus—interpreted as a divine sign to settle here. That iconic image, later enhanced by the Spaniards with the addition of a snake in the eagle’s beak, is now the national emblem of Mexico. For the Aztecs, this location was believed to be the center of the universe.

Over time, the temple was rebuilt and expanded at least seven times, with each new layer often consecrated through ritual sacrifices of captured warriors. Today, visitors can see remnants of all seven construction phases, centered around a platform dating to around 1400. The southern section features a sacrificial stone before a shrine to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. To the north, a chac-mool (a reclining stone figure from Maya tradition) stands before a shrine dedicated to Tláloc, the rain and water god. When the Spanish arrived, a towering 40-meter pyramid with twin staircases led to shrines for both deities.

Visiting the Site

The entrance to the Templo Mayor archaeological zone and its museum lies just east of the cathedral, across the lively Plaza del Templo Mayor. Much of the ruins can be seen from outside, but full access requires a ticket. Authorized guides with official Sectur ID are available at the entrance for tours.

Museo del Templo Mayor

Admission includes access to the excellent on-site museum, which houses an impressive model of ancient Tenochtitlán and a wide range of artifacts unearthed during excavations. While the museum signage is mostly in Spanish, the ruins themselves offer more bilingual interpretation.

One of the museum’s standout exhibits is the monumental Coyolxauhqui stone, best viewed from above on the top floor. The sculpture shows the goddess decapitated—slain by her brother Huitzilopochtli, who also killed their 400 siblings as he rose to divine dominance in Aztec mythology.

Ongoing Discoveries

Excavations at Templo Mayor continue to reveal new and remarkable finds. In 2006, archaeologists uncovered a massive stone carving of the earth goddess Tlaltecuhtli, now displayed on the museum’s first floor. In 2011, a ceremonial platform believed to be used for cremating Aztec rulers was discovered, dating back to 1469. That same dig revealed what is believed to be the trunk of a sacred tree at a burial site near the temple’s base.

Perhaps the most chilling discovery came in 2017, when a 6-meter-wide tower constructed from more than 650 human skulls was found—likely the legendary Huey Tzompantli described by Spanish conquistadors. The remains included not just men, but also women and children, expanding our understanding of sacrificial practices.

In 2019, archaeologists found two richly symbolic burial sites: one of a boy dressed as Huitzilopochtli, the other of a jaguar clad in warrior attire. These finds have sparked fresh hope of uncovering royal Aztec tombs, which have so far eluded researchers.

New Exhibits

A newer public hall now displays recent discoveries from the ongoing excavations—funerary objects, bones, colonial-era porcelain, and pre-Hispanic elements tied to Cuauhxicalco, or “place of the eagle vessel.” These additions keep Templo Mayor an ever-evolving destination, drawing in both first-time and returning visitors.

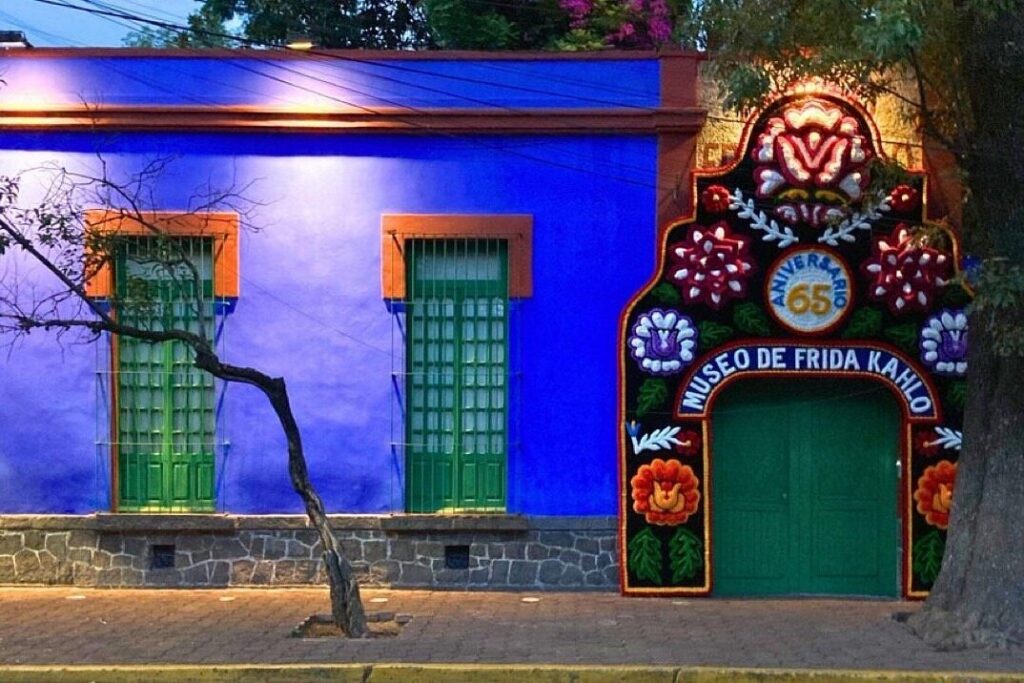

Frida Kahlo, one of Mexico’s most iconic artists, was born, lived, and died in Casa Azul—the Blue House—which now serves as a museum in her honor. A visit here is considered a must for anyone exploring Mexico City, offering a deeper look into Kahlo’s personal and artistic world (and yes, there’s even a gift shop where you might find a Frida-themed handbag). To avoid long waits, especially on weekends, it’s best to arrive early and book tickets online in advance.

The house was built by Frida’s father, Guillermo Kahlo, just three years before her birth. Today, its vibrant interiors are filled with personal items that reflect her complex life, including her passionate and often turbulent relationship with fellow artist Diego Rivera. Everyday objects—like kitchen tools, jewelry, and family photos—are placed alongside artworks, traditional Mexican crafts, and pre-Hispanic artifacts, giving visitors an intimate view of her life and influences.

In 2007, a trove of previously unknown belongings was discovered hidden in the house’s attic, greatly enriching the museum’s collection. Many of these items feature in the ongoing exhibit Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo, which opened in 2012. The exhibit showcases her distinctive clothing, including her signature Tehuana dresses and the orthopedic corsets she was forced to wear after a near-fatal accident. Together, they offer insight into how her disability, fashion choices, personal identity, and artistic vision were all deeply interconnected. A version of this exhibition gained international attention during its 2018 run at London’s V&A Museum.

Kahlo’s artwork—filled with emotional intensity, physical pain, and political conviction—is displayed throughout the home. Around her bed hang portraits of communist figures like Lenin and Mao, reflecting her lifelong flirtation with socialist ideals. In one of her paintings, Retrato de la familia (Family Portrait), she creatively intertwines her mixed Hungarian and Oaxacan heritage.

Casa Azul is located in the charming neighborhood of Coyoacán. It’s a scenic 1.5-kilometer walk from the Coyoacán Metro station to the museum.

If you’ve seen the film Frida (2002), this striking museum may look familiar. It was designed by architect and painter Juan O’Gorman, a close friend of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. The couple lived here between 1934 and 1940, each in their own distinct space—an architectural reflection of their interconnected yet independent lives.

The property includes three houses: one for Rivera, one for Kahlo (painted in her signature blue), and one for O’Gorman himself. Rivera’s house still contains his upstairs studio, filled with personal art tools and whimsical papier-mâché figures. Frida’s and O’Gorman’s homes, meanwhile, have been cleared to host rotating exhibitions.

A narrow bridge connects Rivera and Kahlo’s homes, symbolizing their bond and individual autonomy. From here, it’s just a 15–20 minute taxi or Uber ride to Kahlo’s other famed residence, the Casa Azul (now the Museo Frida Kahlo) in Coyoacán.

Just across the street is the San Ángel Inn, a former pulque hacienda that now operates as a renowned restaurant. It’s also a historic landmark—the site where revolutionary leaders Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata famously agreed to divide power over Mexico in 1914.

You can reach the museum via a pleasant 2-kilometer walk or a short taxi ride from the La Bombilla Metrobús station.

The former home of exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky is now a museum, preserved much as it was on the day in 1940 when a Soviet agent, Ramón Mercader, fatally attacked him with an ice axe. Just off the central patio, visitors can explore exhibitions of personal memorabilia and historical notes, while in the garden stands Trotsky’s tomb, marked with a hammer and sickle and containing his ashes.

After losing the power struggle to Stalin, Trotsky was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1929 and sentenced to death in absentia. In 1937, he and his wife, Natalia, found asylum in Mexico. They initially stayed at Frida Kahlo’s Blue House but later relocated a few blocks northeast following a rift with Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Inside the house, bullet holes in the bedroom walls are a chilling reminder of an earlier, failed assassination attempt. The simplicity of the home, combined with these visible scars of political violence, gives the museum a powerful sense of history.

Entry is via the rear of the property, facing Avenida Río Churubusco. Be sure to ask at the entrance about free guided tours in English, which are often available.

A major religious and cultural symbol in Mexico, the Basílica de Guadalupe draws millions of pilgrims each year. The devotion began in December 1531, when an Indigenous convert named Juan Diego reported a vision of the Virgin Mary on Tepeyac Hill (Cerro del Tepeyac). According to tradition, the Virgin asked for a shrine to be built in her honor. When Juan Diego presented the bishop with his cloak—bearing her image miraculously imprinted on the fabric—the request was granted, and a small chapel was constructed on the hill.

Over time, the Virgin of Guadalupe—Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe—became closely associated with national identity and faith in Mexico. Her depiction with mestiza features helped foster the spread of Catholicism among Indigenous peoples. Though some clergy criticized the cult as a Christianized version of the Aztec mother goddess Tonantzin, she was officially declared the patroness of Mexico in 1737. Later, she was named patron of Latin America and “Empress of the Americas.” In 2002, Pope John Paul II canonized Juan Diego, further cementing the site’s significance.

The sanctuary has grown to encompass a complex of shrines and chapels on and around Tepeyac Hill. The original 1700s church, now known as the Antigua Basílica, eventually became too small for the massive crowds, and in the 1970s a much larger modern sanctuary was constructed beside it. The Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, designed by Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, is a vast circular space capable of holding over 40,000 people. At its heart, the famed cloak—la tilma—bearing the Virgin’s image is displayed above the main altar, and visitors pass beneath it on moving walkways.

Mass is held hourly, and devotion peaks each year in the days leading up to December 12, the Virgin’s feast day, when hundreds of thousands of pilgrims arrive—many completing the final stretch on their knees.

Behind the old basílica is the Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe, which houses a notable collection of colonial religious art inspired by the apparition. From there, a stairway climbs about 100 meters to the Capilla del Cerrito (Hill Chapel), traditionally believed to be the exact spot of Juan Diego’s vision. The route then descends past the Parque de la Ofrenda, featuring gardens and waterfalls around a sculpted depiction of the Virgin’s appearance.

At the foot of the hill stands the Templo del Pocito, an 18th-century baroque chapel with a unique circular plan and tiled domes, marking the site of a spring that appeared at the Virgin’s feet. Nearby is the Antigua Parroquia de Indios, a 17th-century parish built to serve Indigenous worshippers.

Getting there:

Take Metro Line 6 to La Villa–Basílica station and walk two blocks north along Calzada de Guadalupe. Tourist bus services like Capital Bus and Turibús also include stops near the site.

One of Mexico City’s most iconic landmarks, the Metropolitan Cathedral is an architectural masterpiece that dominates the north side of the Zócalo. Measuring 109 meters long, 59 meters wide, and rising to a height of 65 meters, it’s a vast structure whose construction spanned nearly 250 years—from 1573 through the end of the colonial era. As a result, the cathedral showcases a blend of architectural styles, with each generation of builders adding new elements that reflected the innovations of their time.

In a symbolic act of conquest, the Spanish ordered the cathedral to be built directly atop the sacred Templo Mayor, using many of the Aztec temple’s stones for its foundation and walls—a visual and material statement of domination.

Upon entering, visitors are greeted by the intricately carved and gilded Altar de Perdón (Altar of Forgiveness), near which worshippers often gather before the Señor del Veneno (Lord of the Poison). According to legend, this dark-toned Christ figure turned its deep hue after miraculously absorbing poison meant for a priest—transmitted through a kiss from an enemy.

Behind the main altar lies the cathedral’s artistic centerpiece: the Altar de los Reyes (Altar of the Kings), an opulent 18th-century gilded structure dedicated to royal saints. Along the sides of the cathedral, fourteen ornately decorated chapels offer quiet reflection, while in the central nave, late-17th-century wooden choir stalls—carved by master artisan Juan de Rojas—showcase exquisite craftsmanship. The sacristy, the oldest part of the cathedral, features massive paintings by colonial-era artists Juan Correa and Cristóbal de Villalpando.

Visitors are welcome to explore the cathedral freely, though it’s asked that you refrain from wandering during Mass. A small donation is suggested for entry into the golden Sacristía Mayor (open 2pm–4:45pm) and the crypt (11am–5pm, closed Thursdays), where guided explanations are offered. You can also ascend the campanario (bell tower) for panoramic views of the city for M$20, though it was closed for repairs at the time of writing.

Mass is celebrated daily, with the Archbishop of Mexico City presiding over the noon service on Sundays.

WhatsApp us