Nowhere else on Earth matches the raw, breathtaking beauty of this immense white wilderness—an elemental world of snow, ice, water, and rock. Antarctica is truly awe-inspiring.

Stepping into Scott’s hut from the Terra Nova expedition is like walking into a living museum, steeped in an overwhelming sense of history. Outside, dog skeletons lie bleached under the Antarctic sun, a stark reminder of the tragic end of Scott’s return from the South Pole. Standing at the head of the wardroom table, it’s easy to picture the iconic photograph of Scott’s final birthday — his men gathered around a feast, with their flags draped behind them.

Erected in January 1911 on what Scott named Home Beach, the prefabricated structure sits near the edge of McMurdo Sound. Measuring 14.6 meters long and 7.3 meters wide, it’s the largest of the three historic huts on Ross Island. Though it housed 25 men in cramped conditions, the space was ingeniously organized. In front of the main hut stands a narrow building that once served as latrines, with separate sections for officers.

After Scott’s expedition, the hut became a refuge once more — this time for ten members of Shackleton’s Ross Sea party, stranded in May 1915 when their ship, Aurora, broke from its moorings. Their grueling mission was to lay supply depots for the Endurance team, which never arrived due to the ship’s destruction. These men endured 20 harsh months at Cape Evans before being rescued.

To enter the hut, visitors pass through an outer porch area. To the left are the stables along the beachfront. The porch still holds relics of the past: penguin eggs, piles of seal blubber, tools on the walls, and geologist Griffith Taylor’s bicycle.

Inside, the main room — known as the mess deck — was insulated with seaweed sewn into jute bags. Following Royal Navy traditions, Scott maintained a clear divide between officers and enlisted men. The mess deck was home to the likes of Crean, Keohane, Ford, Omelchenko, and others. On the right lies the galley, with its sizable stove.

Beyond a wall once made from packing cases is the wardroom. At its rear is the darkroom and Ponting’s bunk. To the right, you’ll find the laboratory and bunks for Wright and Simpson. To the left of the wardroom table were (from front to back): Bowers (top bunk) and Cherry-Garrard (bottom); Oates (top, with no bunk below); and Mears (top) with Atkinson (bottom). On the right side: Gran (top) and Taylor (bottom); a small geology lab; Debenham (top, nothing beneath); and Nelson (top) and Day (bottom). Day’s bunk later housed Dick Richards during Shackleton’s party, who scratched a somber note into the wall:

RW Richards August 14th, 1916

Losses to date –

Hayward

Mack

Smith

In the back-left corner lies the heart of the hut — Scott’s private area. His bunk is set apart from Wilson’s and Edward Evans’ by a work table, still holding an open book and a faded stuffed emperor penguin.

The hut remains filled with period artifacts: provisions, photographic equipment, and original packaging — many brands still recognizable today. The air carries a musty scent reminiscent of old books and pony straw. A highlight is the telephone once connected to the Discovery hut via bare wire stretched across the sea ice.

From 2008 to 2015, the Antarctic Heritage Trust conducted an extensive restoration of the site. Today, around 700 to 800 visitors land at Cape Evans each year, making it the most visited historic site in the Ross Sea region. To protect its fragile contents, only 12 visitors may enter the hut at one time, and just 40 are allowed ashore at once.

Erected in February 1908 during Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition, the hut at Cape Royds offers a deeply atmospheric experience despite its modest size. Fifteen men once lived here—far fewer than in Scott’s larger hut at Cape Evans—but unlike Scott’s party, every one of Shackleton’s men returned safely. They may have departed in haste, though: when the Terra Nova expedition visited in 1911, they found socks still hanging to dry and an unfinished meal on the table.

Years later, members of Shackleton’s 1914–17 Ross Sea party stopped by to scavenge supplies—tobacco, soap, and other essentials. Between such visits, the hut stood silent, eventually filling with snow. It wasn’t until a comprehensive conservation project by the Antarctic Heritage Trust (AHT) from 2004 to 2008 that the structure was restored, preserving its weathered but evocative charm.

Visitors today should duck upon entering—the original acetylene generator hangs low above the doorway, once used to power the hut’s lamps. Shackleton ran his camp differently from Scott’s: there was no division between officers and men. Still, as “The Boss,” Shackleton claimed a tiny private room near the front. Inside, ask your guide to show you the headboard of his bunk—a packing crate marked “Not for Voyage,” with a signature attributed to Shackleton scrawled upside down on it.

At the rear of the hut, a large cast-iron stove remains, complete with a skillet still holding a freeze-dried buckwheat pancake. A tea kettle and cooking pot sit nearby, with shelves lined with colored-glass medicine bottles. Toward the back, one of the few remaining bunks still holds a fur sleeping bag. Scattered across the floor are food tins with curious labels—Irish brawn, boiled mutton, lunch tongue, pea powder—alongside bright red tins of Price’s Motor Lubricant. A bench on the right overflows with mitts and boots. The original dining table, which was lifted nightly to create space, is missing—likely burned later for fuel.

A remarkable discovery came in January 2010, when conservators unearthed three crates of Shackleton’s Mackinlay’s whiskey and two of brandy beneath the hut. After being thawed in Christchurch, the whiskey was analyzed and faithfully recreated by the master blender at Whyte & Mackay in 2011.

Outside the hut lie the ruins of the pony stables and a garage built for the Arrol-Johnston—the first motorcar ever brought to Antarctica. Though the Siberian ponies could haul loads, they lacked the endurance of sled dogs. You can still see spilled pony oats, a weather-beaten car wheel propped against supply crates, and two wooden doghouses nearby.

The hut’s south side has faded to a graceful silvery grey. Rusted food tins stand in weathered crates—one of them literally spilling its beans. Overhead, cables anchor the hut against fierce Antarctic winds. A new roof, installed in 2005–06, and a replicated Scots pine front door help protect the structure for future generations.

Today, Cape Royds is the least visited of the historic Ross Island huts, with about 700 visitors per year. For conservation purposes, only eight people may enter the hut at a time, and no more than 40 are allowed ashore.

Construction of the current Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station was carried out in phases, with the first group of residents moving in by January 2003. The station was officially inaugurated in January 2008, and full-scale summer operations commenced in October 2011. This advanced, 6039-square-meter facility spans 128 meters in length and features an aerodynamic, elevated design that channels prevailing winds to help prevent snow accumulation beneath it. It can house up to 150 people during the summer season and 50 during the winter.

The station consists of two blue-gray, horseshoe-shaped modules joined by flexible walkways. Built on stilts, these modules can be raised to counter snow buildup. The main entrance, known as “Destination Alpha,” faces the skiway, while a secondary entrance at the rear is referred to as “Destination Zulu.”

One module serves as the residential wing, featuring sleeping quarters, a dining area, a bar, a hospital, laundry, store, post office, and even a greenhouse—officially called the “food-growth chamber”—lending the facility a space-station-like vibe. The second module houses offices, laboratories, computer rooms, telecommunications, an emergency power plant, meeting rooms, music rooms, a gym, and quiet reading areas and libraries throughout.

Engineered to withstand extreme conditions, the station features triple-pane windows, 200kg stainless-steel exterior doors, and a pressurized interior to block out drafts. On one end of the complex stands a distinctive four-story aluminum tower known as “the Beer Can,” which contains utilities, a stairwell, and a cargo lift.

To harness the continuous summer sunlight, photovoltaic panels are installed. Although a wind turbine was added in the 2009–10 season, the gentle winds of the Polar Plateau make it impractical to rely solely on wind energy without a much larger wind farm.

Before this station, the Pole’s iconic structure was “the Dome”—formally used from 1975 to 2008. Constructed between 1971 and 1975, it was a silver-gray geodesic dome, 50 meters in diameter and 15 meters high. Inside were three two-story buildings containing living, dining, laboratory, and recreation spaces. While the Dome shielded inhabitants from the wind, it was unheated, with a packed-snow floor and an open top for ventilation. Over the years, the structure became increasingly buried and unsafe, suffering from snow pressure, power outages, and fuel leaks. These challenges led to the development of the current above-snow station.

The Dome was gradually dismantled, with its final components removed in 2010 and shipped to Port Hueneme, California. The top portion now resides in the Seabee Museum.

Construction of the present US$174 million station began in 1997 and involved 80 workers—25% of whom were women—working nine-hour shifts, six days a week. During the round-the-clock daylight of summer, three rotating crews worked continuously. Conditions were extreme: exposed metal could burn bare skin, and logistical demands were immense. Hundreds of flights from McMurdo Station ferried materials that had been carefully planned, sourced, and shipped over several years.

This narrow, steep-sided channel—just 1600 meters (5250 feet) wide—stretches for 11 kilometers (7 miles) between Booth Island and the Antarctic Peninsula. Often called the ‘Kodak Gap’ for its breathtaking views, it remains hidden until you’re nearly within it. The Lemaire Channel was first navigated in 1898 by the Belgian explorer Adrien de Gerlache and named after another Belgian explorer known for his work in the Congo.

At times, sea ice blocks access, forcing ships to turn back and detour around Booth Island. At its northern end, the channel is flanked by two towering, rounded peaks at Cape Renard, typically dusted with snow—a dramatic gateway to one of Antarctica’s most scenic passages.

The original Holy Trinity Church in Stanley was tragically destroyed during the great peat slip of 1886—a devastating landslide that claimed two lives and damaged several buildings. In its place, the foundation stone for Christ Church Cathedral was laid in 1890, and by 1892, the new brick-and-stone cathedral stood proudly in its place. With its brightly painted corrugated-metal roof and beautiful stained-glass windows, the cathedral quickly became the most iconic landmark in Stanley.

Inside, plaques line the walls, commemorating local men who served in the British Forces during both World Wars, along with other prominent figures from the Falklands’ history.

The cathedral’s most striking feature is its stained-glass windows. Upon entering through the main door, visitors are greeted by the Post Liberation Memorial Window, which proudly displays the Falklands crest and the islands’ motto: ‘Desire the Right.’ Below it are the crests of the British military forces involved in the 1982 conflict. Further down, three scenes depict important elements of Falklands and South Georgia life: Stanley is symbolized by the Cathedral and the nearby Whalebone Arch; the Camp is represented by a typical farmstead; and South Georgia is shown through the church at Grytviken, framed by its surrounding mountains.

At the opposite end of the same wall is the delightful Mary Watson window, a tribute to a beloved district nurse, portrayed with her bicycle, always ready to serve.

In celebration of the cathedral’s centenary in 1992, parishioners created hand-stitched pictorial hassocks—cushioned kneelers that illustrate many aspects of life across the Falklands. Since then, the collection has grown to over 50 unique pieces, each a vibrant glimpse into the islands’ culture and community spirit.

The vibrant flags of the original 12 Antarctic Treaty nations encircle this red-and-white-striped “barber pole,” topped with a gleaming chrome globe—making it an ideal photo spot. But don’t be fooled—it’s purely symbolic.

Although most scientific facilities at the South Pole are off-limits to visitors—to prevent disruption, contamination, or decalibration—it’s still fascinating to explore the remarkable research being conducted here. The Pole’s unique environment makes it a hub for global science.

Located upwind of the station, the Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO) sits within the Clean Air Sector—an area of pristine atmosphere ideal for studying pollution patterns on Earth. Scientists here monitor changes in the ozone layer, including the infamous “ozone hole.” They’re also using Lidar (light radar) to examine how polar stratospheric clouds form. These clouds play a key role in ozone depletion during the Antarctic spring.

Thanks to its high altitude, frigid air, and minimal moisture, the South Pole is one of the best places on Earth for astronomy. About 1 km from the main station, the Dark Sector is designated free of light, heat, and electromagnetic interference to protect sensitive instruments.

The South Pole Telescope (SPT), an 8-meter, US$19 million instrument, achieved “first light” in 2007. It observes cosmic microwave background radiation to help unlock the mysteries of dark energy, gravitational waves, and the early universe.

BICEP (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) pushes these investigations further by measuring the polarization of that same radiation with unprecedented precision.

The Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO) supports these efforts as well. Named after a pioneering Antarctic astrophysicist, MAPO has housed various instruments, including SPUD, which explores cosmic gravitational-wave backgrounds.

Beneath the South Pole lies one of the most ambitious physics experiments on Earth: IceCube, a US$271 million neutrino observatory. From 2005 to 2010, scientists drilled 86 holes 2450 meters deep into the Antarctic ice, lowering strings of digital optical modules (DOMs)—a total of 5484 volleyball-sized sensors.

These sensors look for flashes of blue light caused when ultrahigh-energy neutrinos collide with ice atoms. Since neutrinos can pass through the Earth itself, IceCube effectively turns the planet into a telescope and the ice into a detector. The project could offer new insights into dark matter, galactic power sources, supernovae, and the mysterious behavior of neutrinos.

Over 250 scientists from 36 institutions worldwide currently analyze data from this incredible deep-space observatory.

Located 7.5 km from the main station, the South Pole Remote Earth Science and Seismological Observatory (SPRESSO) is dedicated to monitoring seismic activity in complete silence. Since 2003, sensitive instruments buried 300 meters deep have been detecting earthquakes—and even underground nuclear explosions—from across the globe.

Antarctica’s naturally low seismic activity makes it an ideal environment for this research. The observatory is so sensitive it can detect vibrations four times quieter than those ever previously recorded. Even the idling or shutdown of construction tractors at the station has been picked up by SPRESSO’s instruments.

Together, these specialized sectors and observatories make the South Pole a silent yet powerful engine of global science—probing the Earth, sky, and space in search of answers to humanity’s most complex questions.

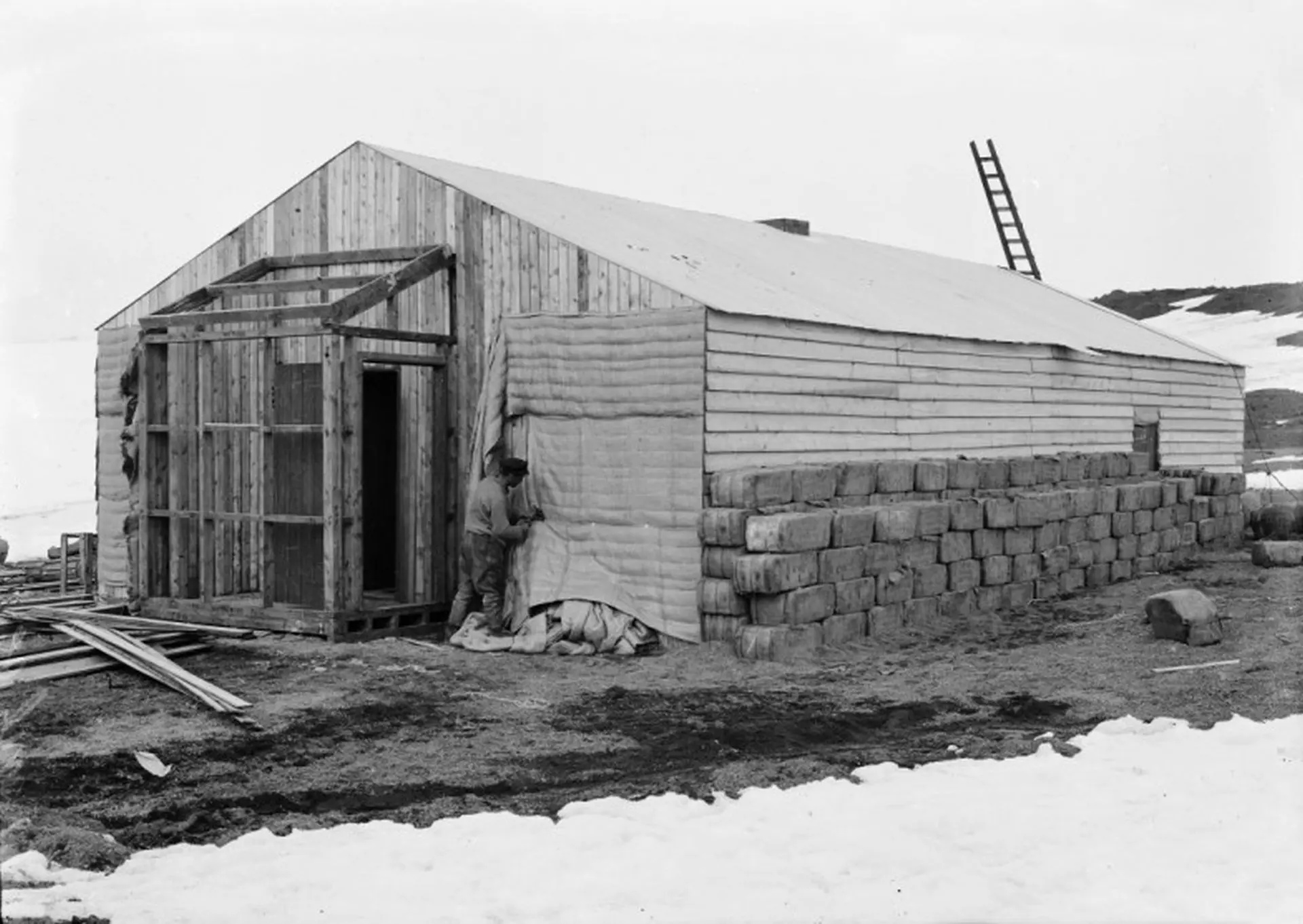

In February 1899, four years after Carsten Borchgrevink first landed here with Kristensen, he returned to Cape Adare—this time as the leader of the Southern Cross expedition. Over the course of two weeks, the team erected two prefabricated huts just inland from Ridley Beach, named after Borchgrevink’s mother. These structures are now recognized as the oldest surviving buildings on the Antarctic continent.

When the Southern Cross ship departed for New Zealand, it left behind ten men who became the first humans to spend a winter in Antarctica. Though isolated, they were not entirely alone—they had 90 sledge dogs, the first ever brought to Antarctica. The team also introduced innovations such as the use of kayaks for sea travel and the Primus stove, a Swedish invention just six years old at the time, which quickly became standard expedition gear and remains in use today.

Life at Cape Adare was far from easy. The party endured a death, a close call with coal-fume asphyxiation, and an almost catastrophic fire. The full story is recounted in Borchgrevink’s First on the Antarctic Continent.

Despite being 12 years older than the huts built by Scott’s Northern Party, Borchgrevink’s shelters have endured better due to their robust construction using interlocking Norwegian spruce boards.

The main accommodation hut, which housed all ten men, measures 5.5 by 6.5 meters. Upon entering, an office-storeroom sits to the left, and a darkroom to the right—both once lined with furs for insulation. Further in, a stove stands on the left wall, followed by a table and chairs. The remaining walls are lined with five double-tiered, coffin-like bunks. Borchgrevink slept in the top bunk at the back-left corner. The hut was insulated with papier-mâché and had just one double-paned window. A charming touch remains overhead—a fine pencil drawing of a young woman on the ceiling above one of the bunks.

The stores hut, located to the west, is now roofless. Inside are boxes of ammunition, which Borchgrevink brought in case of encounters with unknown predators—like polar bears, whose presence in Antarctica he could not rule out. Scattered around the hut are coal briquettes and barrels of provisions.

Today, these historic huts are nestled in the middle of a thriving Adélie penguin colony, and all visitors must take great care not to disturb the birds. The site is maintained by the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust (AHT), and access is strictly limited. Only four people may enter the huts at one time (including an AHT representative), and no more than 40 visitors may be within the hut area at once.

WhatsApp us